What has to happen to improve your relationships at home and at work? What do you think has to happen?

Read the quiz bellow, and then rate your relationships at home, work, or both. Is it hard to decide where to focus? Many people tell me they are very different at home and at work. Of course, there is truth to this, but the key to learning about yourself and creating what you want lies in being able to learn from any of your experiences. To gain the most from this post, focus on whichever situation you want, either at home or at work, and look for the common patterns in your reactions and behavior. The trick is to be able to learn in the midst of any important relationship. Pick one, and rate it. You can always focus on additional relationships later.

To do the rating, pick a number from 1 to io, with 1 representing a low score, or the worst possible condition, and 10 representing the best possible condition. You could pick any number on the scale (a 3 would be not good but not terrible, a 6 would be slightly better than average, etc.):

Now, reflect on the rating that seems most important to you. Describe what is happening in the relationship that leads you to that rating. What would it take for you to give that question a higher rating? Write about what it would take (some people like to write, some do not. While many of the writing assignments in this guide are optional for learning, in this case writing greatly increases the likelihood that you gain what is intended from this exercise, so please write before proceeding further):

Now look at your writing. The language you use reflects your tendencies when it comes to thinking about challenging relationships. Most people are better at critiquing the behavior of others than they are at critiquing themselves. In fact, they are so good at criticizing others that they often have no clue about their own role in whatever is going wrong, and actually believe that the only way for things to improve is if the other person somehow changes.

What’s worse, the behavior of focusing on the other is unlikely to be welcomed, thus further fueling tension in the relationship. The other is likely to respond in kind, focusing their energy on what’s wrong with you. By focusing primarily on how the other could be different, one is essentially saying “this relationship will only be better if you are better.” The key to change is placed outside the self. This focus on the other, which creates a “victim” mentality, pervades modern culture. Allow me to explain.

But first ponder this…a critical skill in adult learning is the capacity for reasonably objective self-critique. This post will offer various means for doing so, as well as tips for getting feedback from others. If you are not willing to study yourself, then this article is not for you.

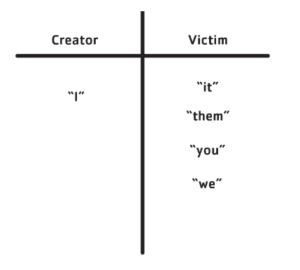

Using the following chart, look at what you wrote about “what it would take to give a higher rating” (or think about what you thought, if you didn’t do the writing), and critique your language. Were you thinking about what you could do differently, or about what others could (or should) do? Were you using “I” language, or other focused language? Were you thinking as a victim or as a creator?

Figure 2: Victim/Creator Model

Before I say more about the difference between a “victim” and a “creator,” take a moment to notice your emotions as you are reacting to this self-assessment. Emotion plays a powerful role in influencing your thoughts, and it’s vital to your development that you recognize your emotional states as clearly as you can. Name your current emotion, if you can. Is your emotional state helping or is it hampering your ability to learn? If you are explaining to yourself why you used “victim” language, and why it’s justified to do so, then you are probably experiencing the emotional state of defensiveness. If this is true and you can see it and admit it, congratulations!

You have the capacity to learn about defensiveness, a normal human reaction, and influence the amount of time and energy you allow that emotion to sway your thoughts and behaviors. If you are feeling defensive and don’t know it (a paradox, but quite possible), then it’s much more likely to be a repetitive experience that interferes with relationships and learning. The clearest indications of this emotional state are behavioral – for example, the behavior of explaining yourself to yourself (in your head, or possibly even out loud) and/or to others. Whenever you begin explaining yourself, it’s a safe bet that you’re acting on the emotion of defensiveness.

Whatever your current emotion, by paying attention to your emotional reaction to the above exercise, we have begun scratching the surface of the critical role that emotional awareness plays in self-awareness, self-development, and relationships. To learn about yourself, it will be vital to explore your beliefs about emotions.

You probably think that some, such as love, are good, and that some, such as defensiveness, are bad. Such beliefs can prevent us from seeing clearly what emotions we, and others, are experiencing. From the perspective of this article, emotion is not inherently good or bad; emotion is simply a constant part of being human. The question is what we do with emotion. If we are unaware of our emotions, we have less control over their impact on our thoughts and behaviors. When we are aware, regardless of what type of emotion is present, we have more influence over what we think and do.

Be careful not to fall into the trap of fooling yourself when looking at the language you used. In creator mode, “I” language indicates speaking for yourself, and taking responsibility for what needs to happen. But one can use the word “I” and remain in victim mode, as in the following examples: “I think my husband should listen more.” “I think if management were more trustworthy, things would be better around here.” These might be reasonable things to want, but you have only shifted out of victim mode if you are looking at your own role in what is happening, and thinking about what you are going to do about it.

Your clarity about the line between victim and creator can also be blurred by the word “we.” There are, of course, times when it is accurate and in good taste to use the word we, as in “we’re all in this together,” and when giving credit to a group when group credit is due (“We got it done”). At other limes, people use “we” in more slippery ways. “We” is used as protection, or to lend weight to an argument, as in “Boss, we all think…” or to claim there’s agreement when there really is not (“We decided…”).

During the exercise, if you said something like, “things will be better when we all start doing our part,” you were still primarily in victim mode. Waiting for “everyone” to change takes the responsibility off of you, even though you are part of the “we.” Figuring out what you’re going to do to start the change, puts you back in creator mode.

If you used “I” language in the exercise, congratulations, you already have the habit, at times of starting with yourself (as, no doubt, do those who used victim language). Keep it up. Increase the habit! And read on. The journey has only begun.